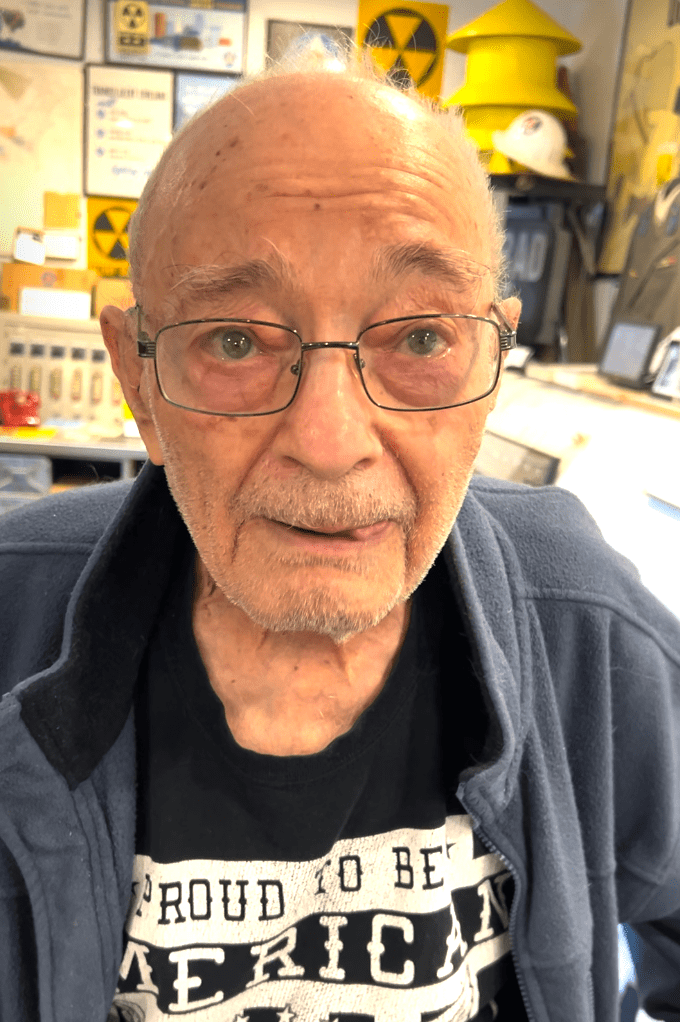

One of the Greek pilots who were recruited by the CIA in 1955 to fly the U-2, has gone public for the first time. Yorgos (George) Tasoulis, 92, gave an interview to a local newspaper in Virginia, where he has lived for most of his life. In July 1956, George and three fellow Greek pilots briefly flew the U-2 at Watertown Strip, the secret test site in Nevada that was colloquially known as The Ranch, before the Agency had second thoughts and opted to continue Project AQUATONE with American pilots only.

I told the story of the Greek pilots for the first time in a post on this website in 2021, with the help of two Greek aviation historians. Now we can amplify the story, thanks to further interviews with George conducted by myself, Kiriakos Paloulian, and Gary Powers Jr, whose father trained to fly the U-2 alongside the Greek quartet. Readers should also refer to my previous post, since I am not repeating here, some of the details that can be found there.

Like his fellow pilots in the Royal Hellenic Air Force (RHAF), George was flying F-84s or F-86s when the call came. The US was looking for pilots with 800 hours jet time for a secret project. It was offering a monthly salary of $400 – quadruple what they were being paid in the RHAF.

Around the middle of 1955, no fewer than 12 pilots were selected for the project, all First Lieutenants with reserve status, which meant that no one might notice if they left the RHAF. They all passed a lie detector test, but three were eliminated before the USAF flew the remainder to Germany, where they stayed for a couple of months. They underwent a thorough medical examination at the USAFE hospital, Wiesbaden airbase. New passports were issued to them, describing them as stateless and using pseudonyms that were allocated to them. George’s “pseudo” was Sophocles Petro.

Then they were flown to Washington DC, where they stayed approximately two months, according to George’s recollection. They were billeted in one of the CIA’s ‘safe houses’ in Culpeper, VA. They were given English language instruction. “We could go into DC, but we always had a ‘minder’ with us,” George said.

One pilot had health problems and returned to Greece. The others proceeded to Palmer House, a historic hotel in downtown Chicago, where measurements were taken for their pressure suits. Then they followed the same path as the American pilots for Detachment A, who were being recruited about the same time in late 1955: pressure suit fitting at The David Clark Company in Worcester, MA; altitude chamber testing at Wright-Patterson AFB, and an exhaustive medical at the Lovelace Clinic in Albuquerque, NM.

In December 1955, the Greek pilots went to Craig AFB for T-33 refresher training– they had already flown the training jet back home.

Most (if not all) of them had flown straight-wing F-84Gs in the RHAF. They were now moved on to Luke AFB to fly the swept-wing F-84F version. It was here that Dimitrios “Jim” Karnezis, a USAF Colonel of Greek origin, helped in their training, including celestial navigation – essential for flying the U-2 on long missions. According to a CIA memo, “if it is decided that we are not going to use these pilots in Project AQUATONE, we feel that we must accomplish some token training in advanced type aircraft”.

But U-2 Project HQ in Washington decided to keep its options open, and send the group on from Luke to The Ranch. But as the ultra-top-secret nature of the project, and the radical design that they were expected to fly was fully revealed to them, four of the pilots opted to quit and return home.

The four who proceeded to The Ranch are now confirmed. In addition to George, they were Ioannis (John) Demopoulos, Sotirios Tsementzis, and Achileas Tzelilis.

The Greek pilots spent only about a month at The Ranch, enough time to complete U-2 ground school, fly some preparatory training flights in a T-33, and solo in the new spyplane. But they each flew only two or three short flights before being withdrawn, and did not progress as far as making any high-altitude flights that required them to wear their pressure suits.

There was a combination of reasons for their departure. One was that Detachment B would be deploying to Adana airbase in Turkey, rather than to a Greek base, as had been originally planned. Relations between Turkey and Greece had been deteriorating for some time, with resident Greeks being expelled from Istanbul and elsewhere. The CIA belatedly realized that Turkey was hardly likely to permit Greek pilots to enter the country and fly over it in such a sensitive operation. In any case, the training of American pilots was well underway, with Det A already deployed to Europe in April 1956, and Det B set to follow in August.

Another reason was continuing language deficiencies, even though the Greeks had gone through language school, and had already been in the US for more than six months, with their flying instruction at Craig and Luke airbases conducted in English.

A third, and contentious reason, was that their flying skills were deemed inadequate. In my previous post, I described a landing accident from which a Greek pilot was lucky to escape. According to Louis Setter, his American instructor pilot, this was the trainee’s first flight, and he was immediately grounded. Lockheed techrep Bob Murphy also recalled a landing accident by a Greek pilot when the undercarriage collapsed.

George describes a difficult landing, which he witnessed from the chase car. But not as serious as described by Murphy. The true story is lost in the mists of time. George thinks the pilot may have been Tzelilis, but he is not sure.

In my previous post, I noted that the USAF Colonel in charge of the group of USAF IPs who were training the CIA recruits, recommended that the Greeks be removed. His recommendation was opposed by two key USAF officers assigned to the CIA for liaison with the Agency’s covert air projects, to no avail.

George disputes the version that the Greek pilots were not good enough to master the U-2’s difficult flying qualities. They just didn’t get much of a chance before they were withdrawn from The Ranch.

The four of them were flown back to Washington, and taken to Ashford Farms, another CIA safe house on the banks of the Choptak River in Maryland. They were debriefed: George says that if they revealed anything about Project AQUATONE, they “would be fined $10,000 and also ten years in prison.” (According to the aviation history website “Greeks in Foreign Cockpits”, none of the pilots who were sent to the US ever said anything about in public their classified mission. Until now).

As a further security precaution, the Agency decided to keep them in the US for 18 months – at the time, Project AQUATONE was not expected to last any longer. The four pilots were offered further education: George took a bachelor degree at the University of Delaware, and a master’s at the University of Pennsylvania.

In the end, only Tzelilis returned to Greece permanently, to resume flying with the RHAF. He was killed in an F-84 crash in 1959. The other three formally left the RHAF in December 1957.

George and the other two stayed in the US. George never flew again. He became a civilian employee of the US government, and specialized in communications. He worked for the Cornell Laboratory on the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) program; the US Navy in Crystal City, and also did a three-year overseas tour with NATO in Europe. He married twice, settled in Virginia, and has one daughter. He lives with his stepdaughter.

Tsementzis also settled in the US, and ran a successful restaurant business. He died some years ago. Demopoulos, back in Greece again, was still alive two years ago, according to acquaintances.

George was persuaded to tell his U-2 story by a neighbour, who arranged for the local newspaper to visit and interview him. I’m sure that I can speak for the entire U-2 Brotherhood in saying to him: Μπράβο! (Bravo!)